The Decline of Hiveworks

The first big tea-spill session of the new year has begun and it’s a fairly big one, involving some major players in the online comic sphere including not just individuals but organizations as well. While this blog normally advocates for smaller, more focused project management, we’re veering off into an unfamiliar mire here in the advocation for a larger, more wide-spread focus, as in this case we’re not talking about project management, we’re talking about the management of projects. That is…a lot of projects.

On the 12th of January, 2026, a statement from a collection of artists who worked with the online comic publisher Hiveworks was released and disseminated among the broader internet. Hosted by the Comics Cooperative, an organization dedicated to advancing opportunities and careers of modern comic artists, the statement was instantly the talk of BlueSky and other major social media platforms. It highlighted a general frustration among Hiveworks “clients” who had worked with the company and in particular its CEO Xel and Second-In-Command, Isa. Their allegations are laid out clearly in their initial paragraphs, stating that the company had not been delivering on their stated offerings and as a result were losing creators, losing staff, and perhaps most importantly: losing money.

Despite having been around for a decent period of time (since 2011), Hiveworks never seemed to rise above the very first levels of company management and spectacularly failed at making the organization financially solvent. In fact the statement provided from the Hiveworks Guild claims that as of now, Hiveworks is in debt to the tune of around $340,000. Though the concept of the business seemed relatively solid and money was flowing through not just ad revenue but through fundraising and centralized shop sales, the Guild became aware of the massive amount of debt some time in the last year. The statement describes internal chaos with examples of robbing Peter to pay Paul: the funding of older projects with newer ones in order to stay afloat. They describe the discovery of a 15,000 dollar embezzlement that occurred in 2023 that had been kept under wraps along with a myriad of other poor financial decisions that seemed to snowball out of control quickly. Xel, the CEO who was, allegedly, only 19 at the time of Hiveworks’ founding, claimed that the business model wasn’t designed to make money and it certainly didn’t, requiring infusions of her personal cash at times in order to keep it from dissolution.

Artists and creators on BlueSky took to the quote reposts to chat about their own personal experiences with the mayhem that was Hiveworks. Creater Sarah Webb explained that her KickStarter project took over six months extra to ship because the organization had essentially stolen her shipping funds to spend them on something entirely unrelated. Comic artist Clover of “Go Get a Roomie” described the vibe of an early Hiveworks just getting its feet under itself (which it never actually seemed successful in achieving), running three simultaneous KickStarters and running almost entirely on the fumes of optimism and naked ambition. Clover’s later optimism was hinged on the idea that Xel, and her inability to control spending or manage finances, was going to be reined in by her staff, including Isa who turned out to be a whole different issue.

Isa, as Second-In-Command and a comic artist herself, took on a huge amount of responsibility within Hiveworks and its NSFW affiliate Slipshine. With an almost pathological inability to delegate responsibility, Isa was piling more and more onto her plate and was constantly overworked and buried in piles of questions from concerned creators who were looking around wondering why things weren’t going as smoothly as they could have been. The answer to this was not just general incompetence, but good old fashioned logistics. Beyond a certain level of scale, things naturally need to be broken up into manageable pieces. Anyone who has played a logistics-based videogame can tell you that certain aspects of movement, supply, and demand, are all aspects that need to be considered—this is the same for project management or, as in this case, the management of projects.

[Here begins my extremely boring explanation of my opinion of ideal management paradigms for creative projects, scroll to next bold bracket to skip]

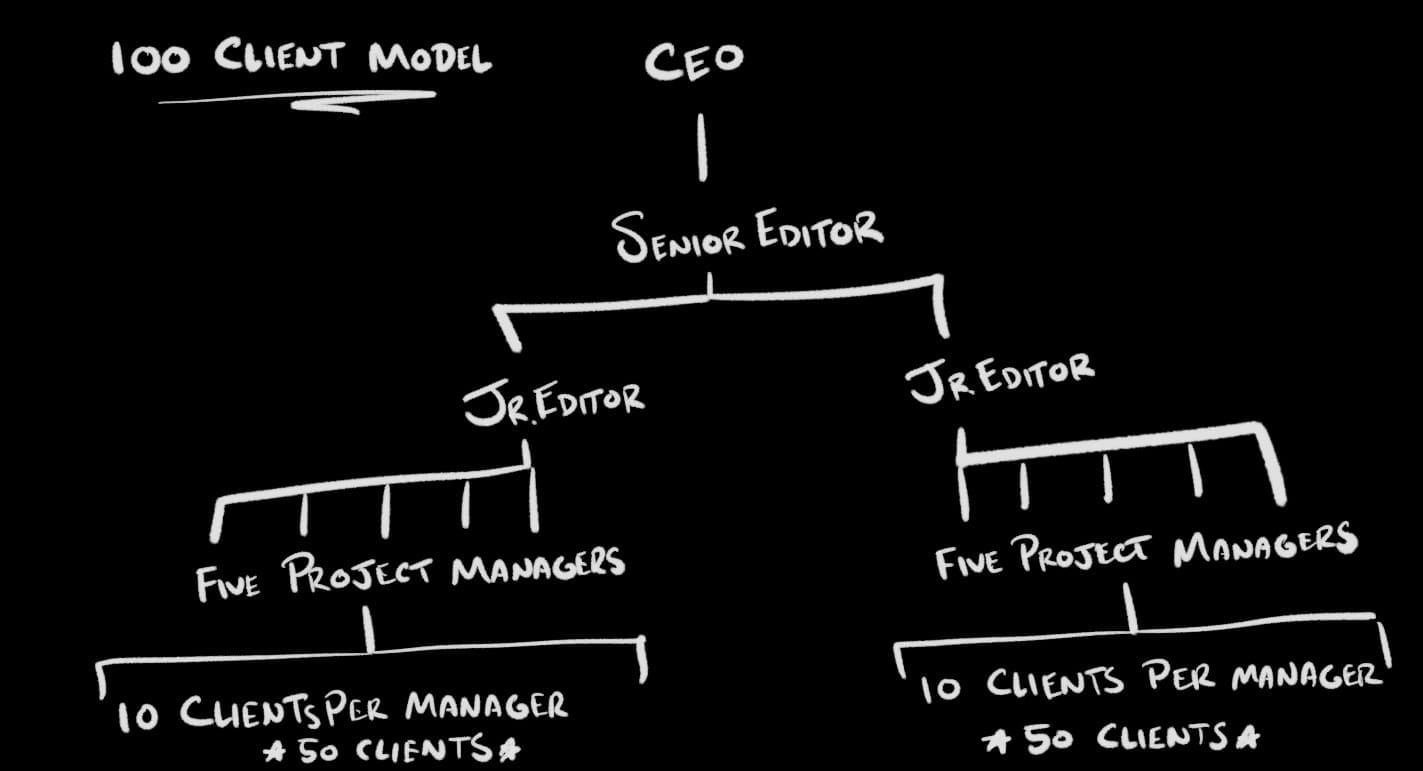

Let’s use a collaborative zine for scale. A zine has only so many moving parts that need to go from one form to another then to another. There are let’s say 10 small projects from ten contributors that are then arranged into one larger project that is then sent to a printer and comes back to be shipped out. This requires no more than 1-3 people who can edit, format, send to the printer, and then ship out. Ten small projects could easily be managed by one person, especially if the works are primarily only hosted digitally and the contributors have access on the backend of a hosting set-up and can manage their own update schedules. If this was a day job and not just a part-time position, one person could probably even manage upwards of 15 to 20 small projects, depending on the attention each one required. This is how you get those nice little hierarchies in companies. Ten clients to one manager, five managers to one supervisor, one Senior Editor to two supervisors and you have a functional web of 100 clients that are now manageable and each step of this model can have clearly-defined duties in regards to authorizations for KickStarters, design decisions, and one-on-one interactions with artists and creators. When the CEO is personally interacting in a Slack or a Discord, especially in an unprofessional manner, and the “Chief Operating Officer” has piled herself so deep in the hats she wants to wear that she can’t work effectively, the weight of hubris at the top starts to impede the efforts of those in the middle and at the bottom.

A company this size seems as though the ideal design would look something like this:

You might even be able to cut out the Jr. Editors if you wanted the Project Managers to take on more of the roles of editing and processing though having the Jr. Editors there makes it easier for them to handle aspects like translation deals and other things the Guild categorized as “administrative” duties. One of the major issues raised was what Hiveworks referred to as the “work queue” which could have been rendered obsolete had they allowed the Project Managers to essentially act as in-org agents, working for the benefit of their artists and managing things like KickStarters and advocacy for their artists’ projects in realms like ad space. This would also prevent talent bleed and mitigate the dubious matter of picking one fundraiser’s pockets in order to fund an unrelated project’s goals by working on those projects simultaneously and separately. Should a project be unable to find individual success in finance, discretionary spending could be considered—but this only works if the org as a whole is financially solvent. Theoretically.

Now, take all this with a grain of salt, as I am but a humble blog writer and business logistics certainly isn’t what I went to school for, though it doesn’t take a genius to pinpoint that there were multiple failings within Hiveworks that could have been mitigated easily with a better management paradigm—one that would have prioritized time management, financial solvency, client agency, and product quality. Some of my absolute favorite online dramas are the implosions of zine projects which somehow end up having 30-40 “mods” (what modern zines call project managers) and a blobular management structure that leads to inevitable communication issues, so naturally I was enthralled to discover that there was an entity with the opposite problem that ended up with similar results.

So if one pitfall is too many middle management types and the other is too few middle management types, is there a sweet spot that we can strive for every time? No! Haha, of course not. We can, nevertheless, not forget that the business side of artistic collective and artistic projects is just as important as the art itself. Knowing the limits of management potential helps to break work up into chunks that do not have to be juggled to be managed and focusing on financial solvency is not compromising artistic merit but providing the scaffolding to support further artistic goals. Determining how many people you need for a project is a skill in itself and breaking them up into a hierarchy with clearly-defined roles that are appropriate for the best client/customer experience goes along with that skill set. If you can’t afford that many people, don’t take on that many clients/projects or prioritize roles and duties to cut down on overhead to have more clients per manager. Grow slow: grow safe. Additionally, keep a lot of major decisions in the hands of project managers and you avoid some of the worst aspects of bureaucracy as well, allowing for creator agency and semi-immediate results.

[Here ends the extremely boring explanation of my opinion on ideal management paradigms for creative works]

I digress. Much of this drama was focused around the mismanagement of Hiveworks as a whole, the personal and professional integrity (or lack there of) of their CEO and COO. Let’s be frank: no CEO should be in the direct messages of clients casually chatting about whatever state of affairs were happening at the time and there is no reason that clients or even middle management should be aware of any medical injuries or maladies are happening above them. Though we’re all human, things can’t simply grind to a halt when paychecks are on the line and no sickness can be considered reason for mismanagement when there could be people who would be able to take over duties. The CEO should not be acting as though fundraisers that are part of their business model are contributing to their personal slush fund, and ideally, a publisher (which Hiveworks later decided they were not) should eventually move away from fundraisers as an onboarding tactic for new projects. Sadly, if you have no discretionary funds, that’s impossible.

The Hiveworks creators who’ve been most affected by this debacle have put together their own web ring (oh my god, remember them!?) and have moved toward a more creator-led advertisement model that prioritizes art over financial gain or stability (at current, all their efforts are 100% volunteer-based). Though things like Hiveworks might have had the possibility of allowing artists to survive off ad revenue—at least for a short time—and had the potential to create a larger audience pool, it seems as though the cost wasn’t worth the reward. From this point on, it seems that the best thing we can do as bystanders is make certain to add these folks to our RSS readers and keep up with their socials so we can make sure to support all of their current and future projects. I dunno about all of y’all, but I’m a slut for comics and Chimera Comic Collective is exactly my cup o’ tea. So make sure not to discount middle management, remember that money complicates literally everything, and make sure to support creators directly whenever possible!